Flock Safety is a private, venture-backed surveillance company selling camera systems + a cloud search platform to police, cities, businesses, and HOAs.

Public debate is not “anti-law enforcement” — it’s democracy in action: residents asking how a private vendor’s database is governed, audited, shared, retained, and paid for with tax dollars.

FLOCK SAFETY • PRIVATE SURVEILLANCE VENDOR • PUBLIC RECORD

Who is Flock Safety?

Flock markets its technology as “public safety,” but it operates as a paid data platform: cameras capture images + metadata, upload to a private cloud dashboard, and access to that database (and its analytics) is sold through subscriptions.

This page collects public documents, news, and vendor statements so residents can evaluate Flock as what it is: a private company asking for public trust, public siting, and public money — while residents ask basic constitutional and governance questions.

- Flock is venture-backed and built around recurring subscription revenue.

- Growth metrics matter: renewals, network expansion, and upsells.

In a published city document, the CEO framed criticism and public-records scrutiny in combative terms (e.g., describing a “coordinated attack” and “weaponizing FOIA”). That style of framing is not evidence of safety — it’s evidence the company treats oversight as a threat to the business relationship.

Staunton, VA email exchange (PDF)

Flock’s leadership messaging frames public-records scrutiny as an “attack,” and the company’s own customer communications describe product / policy changes that reduce what can be independently verified through audit history.

When a surveillance vendor responds to scrutiny by limiting “audit” visibility, that is a transparency risk — not a safety feature.

That makes it harder for the public (and sometimes even the agency) to prove proper use, detect misuse, or evaluate sharing and retention practices.

- What exactly changed in “Network Audit” or audit-history visibility, and on what date?

- Can our agency still export complete audit logs internally (even if public releases are redacted)?

- Did the City/PD enable any new opt-in sharing settings (including federal opt-in)? If yes, who approved it and when?

- What written policy governs retention, sharing, Safe List use, and who can search?

- What independent audit or oversight exists to detect misuse?

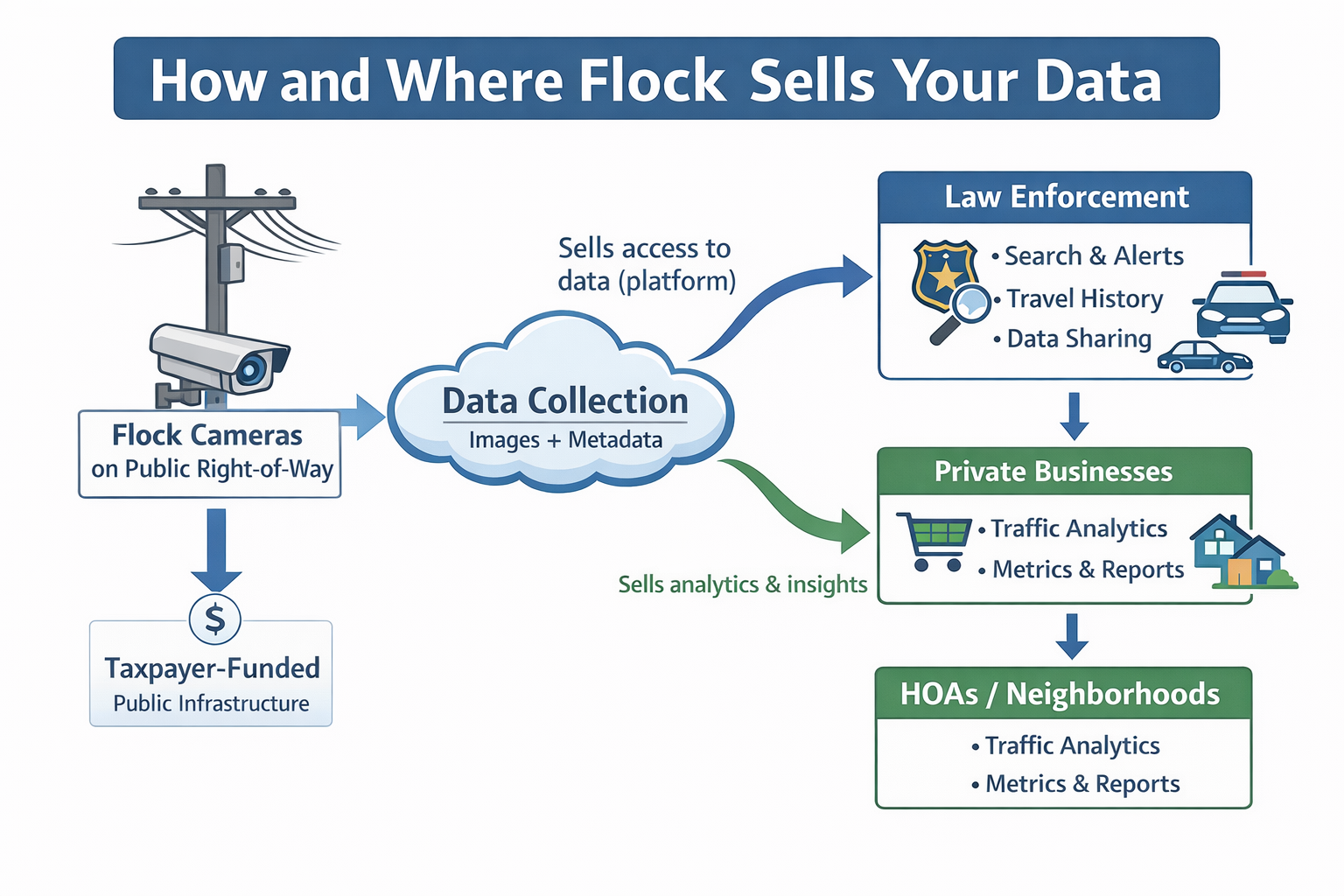

💰 How and Where Flock Sells Your Data

Flock markets itself as a “public safety” tool, but the system operates as a paid data platform: cameras capture images + metadata, data is uploaded to a private cloud dashboard, and access to that database (and its analytics) is sold through subscriptions.

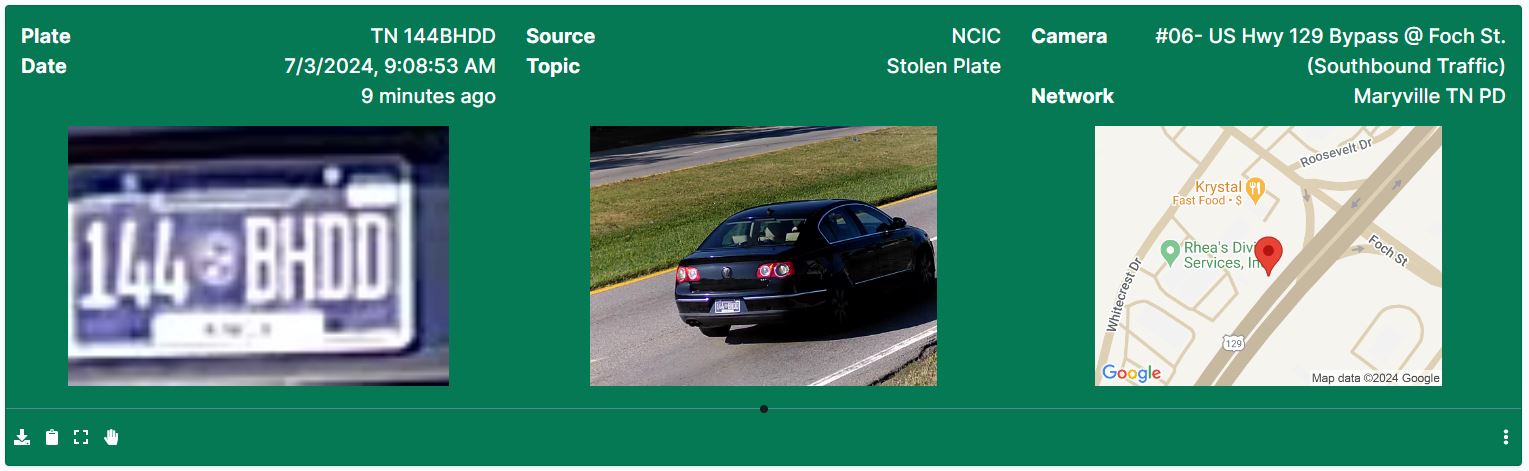

Flock doesn’t “only capture criminals.” It captures everyone who drives past: a vehicle image plus time/location metadata (as shown in platform interfaces) — creating a searchable database of public movement.

Oversight questions aren’t hypothetical; they’re about what happens when routine travel becomes retained, searchable, and shareable at scale.

What’s documented in Maryville / Alcoa (local focus)

- Public infrastructure siting: cameras are installed on poles and roadside locations that exist because taxpayers fund and maintain public infrastructure.

- Law enforcement access: the city pays for platform access that includes searching, alerts, and travel-history-style lookups (as reflected in portal screenshots, dashboards, and training materials published on this site).

- Analytics about the driving population: dashboards can show aggregate breakdowns across the city, not just “suspect vehicles.”

What we’re actively investigating

- Private network expansion: community observations indicate cameras operating in private retail lots and HOA settings, creating a public/private surveillance web.

- Access requests to private cameras: publishing records showing when/how local agencies request access to private lot systems.

- “Not personal data” language: reviewing contracts/terms for how “anonymized/aggregated” is defined and what rights the vendor keeps.

(Click to view larger)

(Click to view larger)

Note: This section documents system workflow and siting transparency. It is not an allegation about any individual driver. Purpose: illustrate how the system works (capture → record → map → alert) and why policy on retention, access, and audits matters.

🧠 Flock’s patent: surveillance capabilities, not “public safety” slogans

Flock’s branding centers “public safety,” but the patent record is blunt about what the system is designed to do: collect information from cameras in public space, extract identifying attributes, store those results with time/location context, and make them searchable across a wide area. That is the definition of a surveillance platform.

The most important takeaway is not “AI” — its scope. A license plate reader implies “targeted” use. A patent describing distributed cameras + a cloud database implies something else: routine capture of everyday Americans going about normal life (school pickup, commuting, grocery runs), because the system must capture everyone in order to work as advertised.

Quick keyword snapshot (Patent: U.S. 11,416,545)

This is not “only about criminals.” It is a system built to collect on the general public first — then allow searching later. The city’s real responsibility is not to repeat vendor slogans, but to publish enforceable rules for: retention, who can search, what justification is required, who results can be shared with, and audit logs that can prove those rules are followed.

That’s why this matters in Maryville and Alcoa: “public safety” is a goal, but surveillance is a capability. The patent describes capability. Residents are left to demand what should have been published from day one: written policy, public reporting, and auditable accountability.

Transparency note: this section cites the patent record to describe capability and scope. It does not accuse any individual resident of wrongdoing.

🧾 Staunton, Virginia: CEO email + police chief response

Staunton published a document showing an unsolicited email from Flock’s CEO framing criticism and records requests as a “coordinated attack,” and a police chief response explaining that citizen concerns and questions are “democracy in action.”

- It frames critics as activist groups who want to “defund the police,” and characterizes public-records activity as a “weapon.”

- It positions Flock and police as a single team (“fighting this fight for you”).

- It uses emotional language (“tough every day waking up to stories online…”) rather than sticking strictly to verifiable facts and contract terms.

The chief describes citizen concerns about surveillance and data use as democracy in action, not an “attack.”

That distinction matters: asking questions about a private mass-surveillance vendor is not anti-police.

🏗️ A startup scaling into public infrastructure

Flock scaled quickly from a startup model into public infrastructure deployments (public right-of-way, utility/pole siting, and roadside installations).

When a private company’s hardware ends up on taxpayer-maintained infrastructure, residents can reasonably ask to see permits, right-of-way agreements, liability coverage, and data-use limits — in writing.

📌 Reported examples: permitting / approval disputes (non-exhaustive)

- Fort Worth, Texas (public right-of-way / permits):

Investigation reporting described cameras placed on public property without approvals/permits and the city’s response.

Source (KERA) - Florida (state right-of-way / DOT permitting):

Investigation reporting described installations in state right-of-way without required permits and related enforcement actions.

Source (Action News Jax I-Team) - Cambridge, Massachusetts (unauthorized installs):

The City’s own statement described a trust/material breach involving additional cameras installed without the City’s awareness.

Source (City of Cambridge) - Cambridge, Massachusetts (local reporting context):

Local reporting discussed unapproved camera issues and city response.

Source (Cambridge Day) - Evanston, Illinois (policy / legal controversy context):

Local reporting described public controversy and legal/policy questions around access and compliance.

Source (Evanston RoundTable)

✅ Minimum baseline residents can demand

- Proof of permission to occupy public space: permits + right-of-way agreements (PDF copies).

- Liability clarity: insurance, indemnification, who pays if equipment is moved/damaged or interferes with public utilities/maintenance.

- Written rules: retention limits, sharing rules, search justification standards, audit logs, misuse penalties.

- Procurement transparency: contract, renewals, add-ons, analytics modules, and any private-camera partnership terms.

- Vendor contact transparency: who met with the vendor, when, and what expansions were discussed (ALPR → drones → radar, etc.).

📉 The trend: more cities are pushing back

Some cities have suspended deployments or ended agreements when process, community consent, or trust breaks down.

ALPR is not just a camera — it’s governance: search justification, retention, sharing, audit logs, procurement oversight, vendor access, and public reporting.

Cambridge’s statement describes deactivation/removal of ALPRs and a contract termination after additional cameras were installed without the City’s awareness.

Staunton published the CEO email exchange and later published a city news release stating the City would terminate the contract.

When a vendor frames scrutiny as an “attack,” residents can treat that as a governance red flag. A public-records request is not hostility — it’s a normal accountability tool in a democracy.

🧾 Who brought Flock to Maryville, TN? (Officials recorded in the July 2, 2024 approval)

According to the official July 2, 2024 City of Maryville Council minutes and meeting packet, the City Council unanimously adopted a resolution titled

“A RESOLUTION APPROVING THE INSTALLATION OF LPR/CAMERAS IN MARYVILLE, TN FOR THE PURPOSE OF PUBLIC SAFETY.”

The officials below are listed in the public record in connection with that vote and related implementation.

Where an official is publicly associated with a business or professional firm, links are included so residents can evaluate potential incentives and demand written safeguards (without assuming wrongdoing).

- Andy White — Mayor. Presided over the July 2, 2024 meeting and declared the LPR/camera resolution adopted after a unanimous roll call vote.

Questions residents can ask:

-Were privacy safeguards and oversight requirements made public before adoption?

-What written limits exist on retention, sharing, and vendor access? - Fred Metz — Councilmember / Vice Mayor. Made the motion to adopt the LPR/camera resolution.

Questions residents can ask:

-Did the motion include enforceable guardrails (audit logs, retention limits, sharing restrictions), or was it a blanket approval?

-Were cost/renewal and data-use terms fully disclosed to the public prior to the vote? - Tommy Hunt — Councilmember. Seconded the motion to adopt the LPR/camera resolution.

Questions residents can ask:

-Do officials whose businesses rely on distributed retail locations support surveillance expansion that may also benefit their industry?

-Were community privacy impacts evaluated in writing before approval? - Drew Miles — Councilmember. Present at the July 2, 2024 meeting and part of the City Council that voted unanimously.

Questions residents can ask:

-Could any private-sector industry (including insurance or risk analytics) benefit from expanded surveillance or ALPR-derived analytics?

-What written limits prevent sharing or repurposing beyond public safety? - Sarah Herron — Councilmember. Listed in the minutes as absent from the July 2, 2024 meeting and therefore did not participate in the vote.

Questions residents can ask:

-Were later decisions (budget, renewals, policy changes) made with clear public notice and published safeguards? - Greg McClain — City Manager. Listed as present at the July 2, 2024 Council meeting.

- Sherri Phillips — City Recorder. Listed as present; resolution text identifies the Recorder’s role transmitting certified copies to TDOT.

- Melanie Davis — City Attorney. Listed as present; resolution form includes “Approved as to form” signature line.

Questions residents can ask:

-Were enforceable privacy safeguards and data-use limits written into policy/contract (not just informal practice)?

-Are those safeguards publicly accessible and auditable? - Tony Jay Crisp — Chief of Police / Director of Public Safety.

Public records/agenda background state the department has “for numerous years operated LPR/Cameras,” and Flock-related correspondence is addressed to or from his office regarding meetings and implementation details.Vendor influence / relationship transparency issue (documented)A vendor email to Chief Crisp includes: “Thank you for the hospitality last week. It was a blast!”

That matters because the same vendor is soliciting public funding for expanded surveillance (here: a regional drone proposal listing stated costs of $300k (year 1) and $450k (year 2)).

Document summary: Vendor-to-chief sales email proposing a regional “Flock Drones” rollout (launch stations + radar), including pricing and vendor-provided FAA waiver/pilot support.Questions residents can ask:

-What is the department’s written policy on vendor meals/hospitality/gifts?

-Were vendor meetings logged and disclosed?

-Was there an RFP or competitive process for expansions (including drones), and are all quotes/contracts published? - Lt. Rod M. Fernandez — Maryville Police Department.

Email correspondence shows he served as a primary point of contact with Flock Safety, including arranging a March 20, 2024 meeting with a Flock representative and drafting a May 31, 2024 letter to the Electric Department to secure permission needed for camera installation.

- Published written policy: who can search, required justification, retention limits, sharing rules, and audit logging.

- Independent oversight: periodic audits + public reporting (search counts, reasons, hits, sharing, misuse findings).

- Strict limits: retention caps, purpose limitation, and bans on repurposing beyond stated uses.

- Procurement transparency: full contract, total costs, renewals, and add-on analytics products.

- Vendor influence safeguards: written gift/hospitality rules + disclosure of vendor meetings/communications (especially for expansions like drones).

Source: City of Maryville City Council Meeting Minutes, July 2, 2024, agenda background materials, and TPRA-released email records. Business/professional links and “questions residents can ask” are included for accountability and do not allege wrongdoing.

🛡️ Oversight is pro-community — and pro-constitutional policing

MaryvillePrivacy.org is not “anti-police.” It is pro-accountability. Our core position is simple: if a private company is selling a mass-surveillance platform to government, residents have the right to ask how it works, how it’s governed, and how it can be misused.

“Public space” does not mean “no rules.” Oversight questions aren’t about whether a single camera can see you — they’re about what happens when everyone is recorded, retained, searched, shared, and analyzed at scale.

Why vendors blur the line

A vendor benefits when it can equate criticism of the company with criticism of law enforcement. But a private company is not “the police.” A taxpayer has every right to question a private vendor’s claims, contract language, auditability, and business incentives.

✅ What residents should demand before/after any ALPR rollout

- Written policy published publicly: who can search, what justification is required, retention limits, sharing rules, and audit logging.

- Independent oversight: periodic audits + public reporting (counts, reasons, hits, sharing, misuse findings).

- Strict limits: retention caps, purpose limitation, and clear bans on repurposing beyond stated uses.

- Procurement transparency: full contract, total costs, renewals, and any add-on analytics products.

- Vendor influence safeguards: clear gift/hospitality rules + disclosure of vendor meetings and communications (especially for expansions like drones).

- Community consent: hearings before expansion, not after equipment is already in the field.

If officials cannot explain — in writing — retention, sharing, audit logs, and search justification, the system is not ready for deployment.

🎥 Video explainers + primary source

If you’re new to Flock, start with these short explainers — then review the primary source email below.

Video link:

youtu.be/vU1-uiUlHTo

Video link:

youtu.be/hwbE5ks7dFg

Download PDF: “Standing With You — Momentum, Progress, and What’s Ahead” (Chris Colwell, SVP Customer Experience)

❓ Common questions

Is questioning Flock “anti-law enforcement”?

What does “Flock sells your data” mean?

Why do permits and right-of-way approvals matter?

What should my city publish before any ALPR rollout?

Where can I read the Staunton CEO email exchange?

PDF document.

Sources / primary documents:

• Staunton email exchange PDF: https://www.ci.staunton.va.us/home/showpublisheddocument/13448

• Staunton termination news release: https://www.ci.staunton.va.us/Home/Components/News/News/2564/71

• Staunton Chief profile: https://www.ci.staunton.va.us/departments/police/about-us/chief-of-police

• Cambridge termination statement: https://www.cambridgema.gov/news/2025/12/statementontheflocksafetyalprcontracttermination

• CEO LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/glangley/

• Permitting dispute reporting (examples): KERA / Action News Jax / Cambridge Day / Evanston RoundTable (see links in Section 3)

MaryvillePrivacy.org informational page about Flock Safety, an automatic license plate reader (ALPR) and surveillance camera vendor providing cloud-based search, alerts, and analytics.

This page discusses public oversight, public records, data retention and sharing, audit logs, right-of-way permitting, and examples of city contract terminations (Staunton, Virginia; Cambridge, Massachusetts).

It also provides local accountability context for Maryville, Tennessee including the July 2, 2024 LPR/camera approval vote and questions residents can ask about governance, procurement transparency, and vendor influence safeguards. It includes a Maryville, TN example camera location (US 129 Bypass at Foch Street) and a TPRA-released platform screenshot illustrating alerts, timestamping, and map context.